Self-fulfilling prophecies: But is the prophet heard?

Seminar on Prediction Under Intervention(s), Leiden

Department of Data Science Methods, Julius Center, University Medical Center Utrecht

2025-12-02

Prediction model performance versus healthcare impact

- many prediction models: given feature \(X\), estimate probability outcome \(Y\)

- e.g. given age, cholesterol and sex, predict 10-year risk of a heart attack

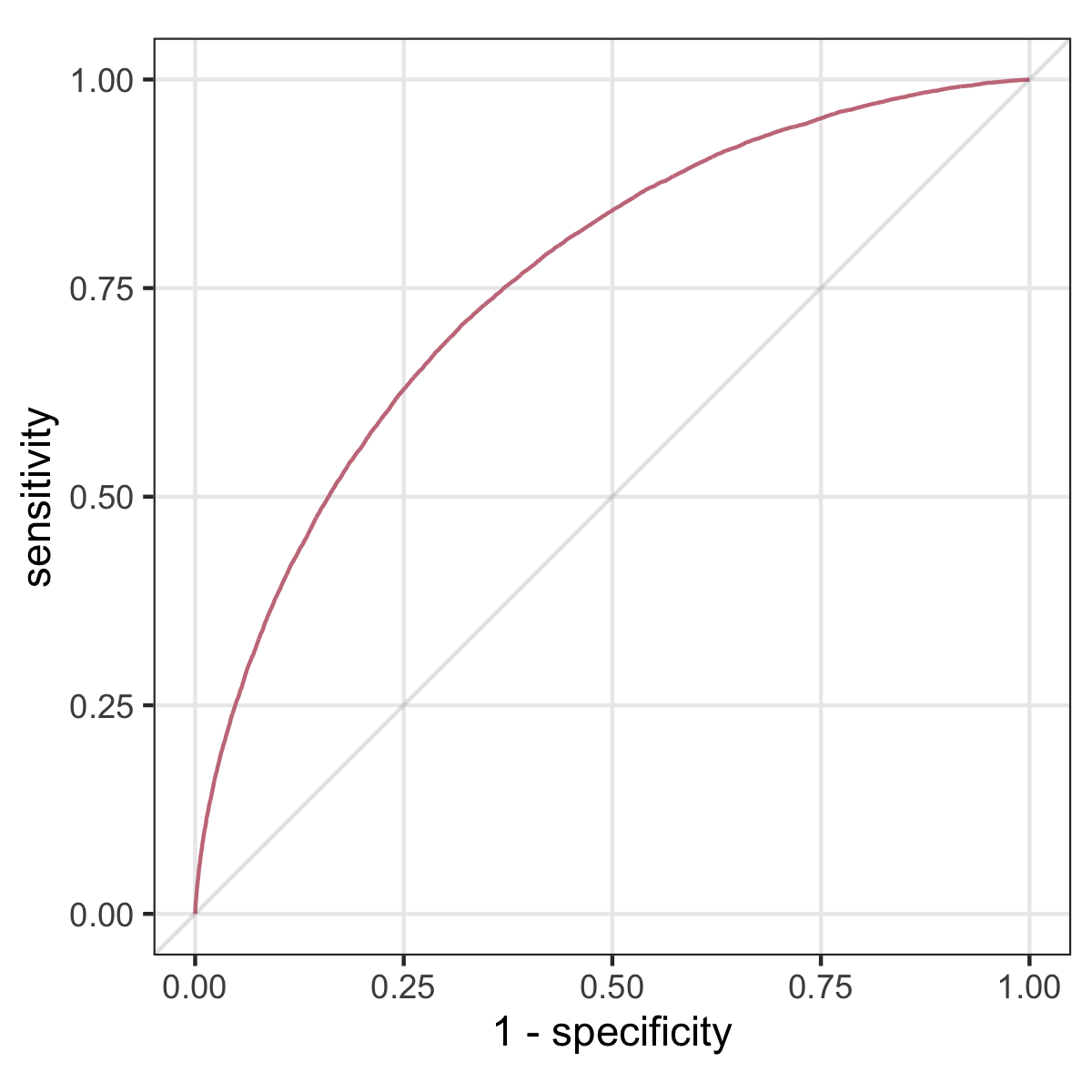

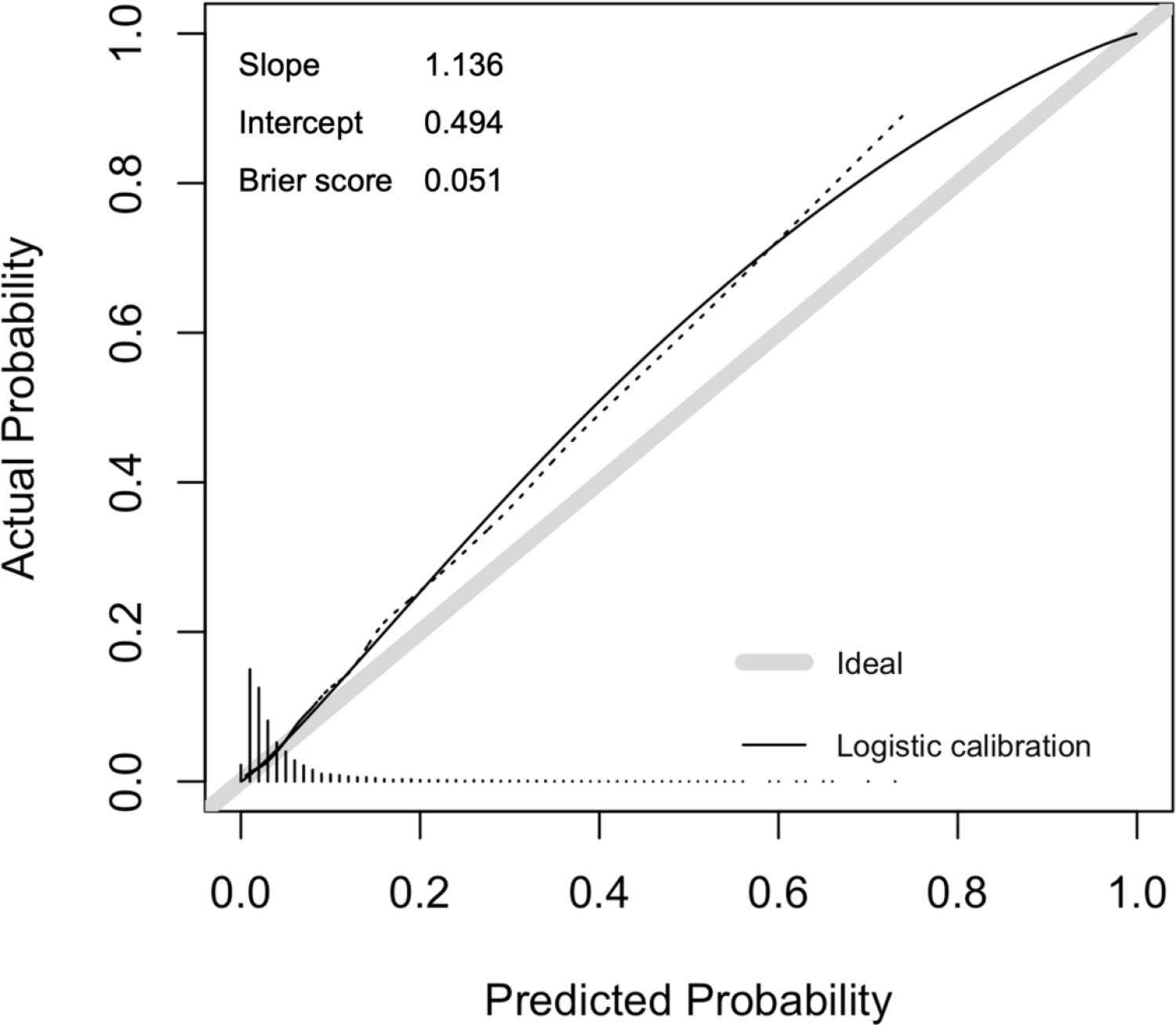

- evaluated on predictive performance: calibration and discrimination (AUC)

Prediction model performance versus healthcare impact

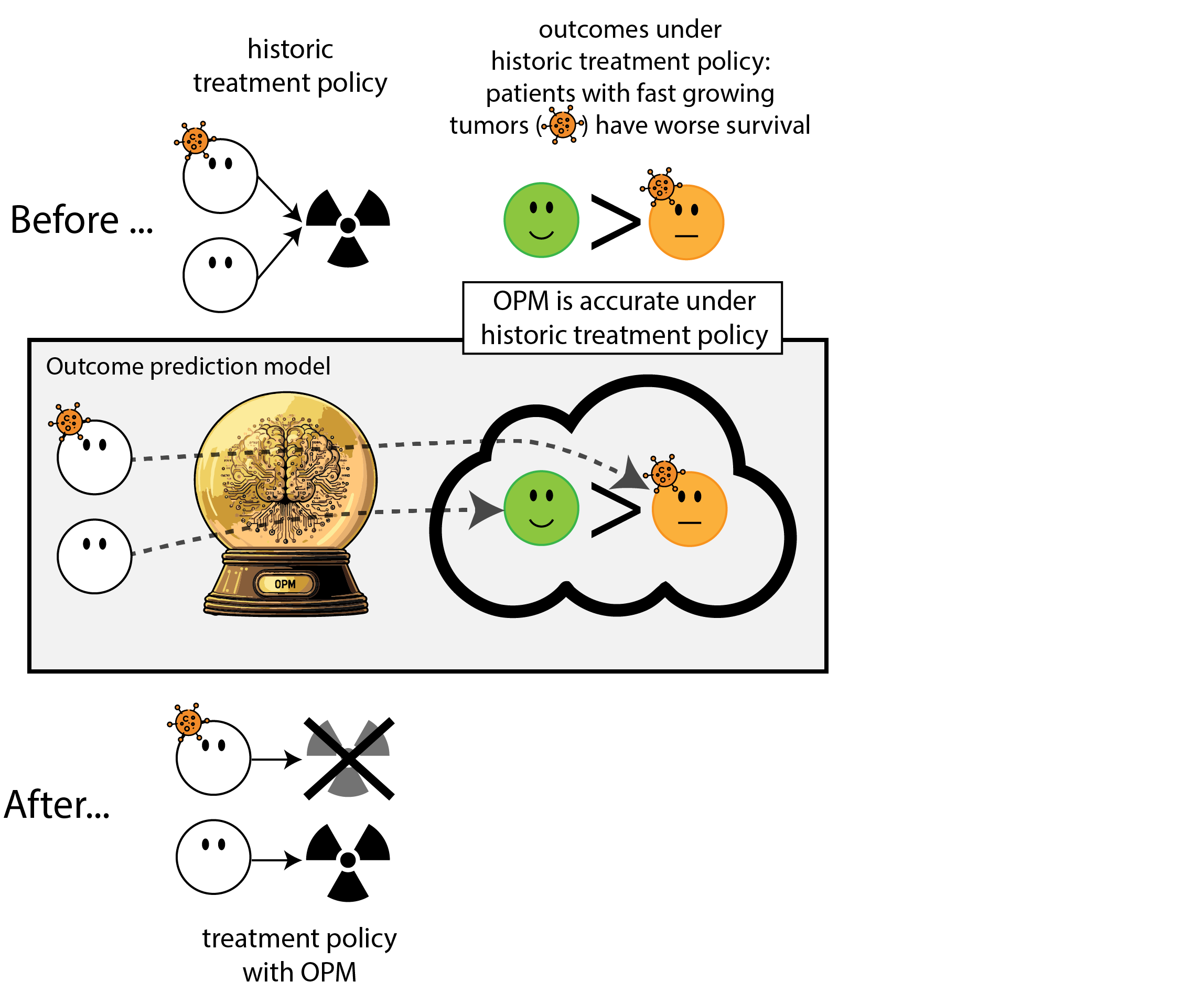

- then used for decision support

- e.g. give statins if predicted risk of heart attack > 10%

- aim: improve healthcare outcomes, without over-treating

- sold as ‘personalized healthcare’, from ‘one-size-fits-all’ to ‘right treatment for the right patient’

- the hope is: better predictive performance \(\implies\) better impact

what could possibly go wrong?

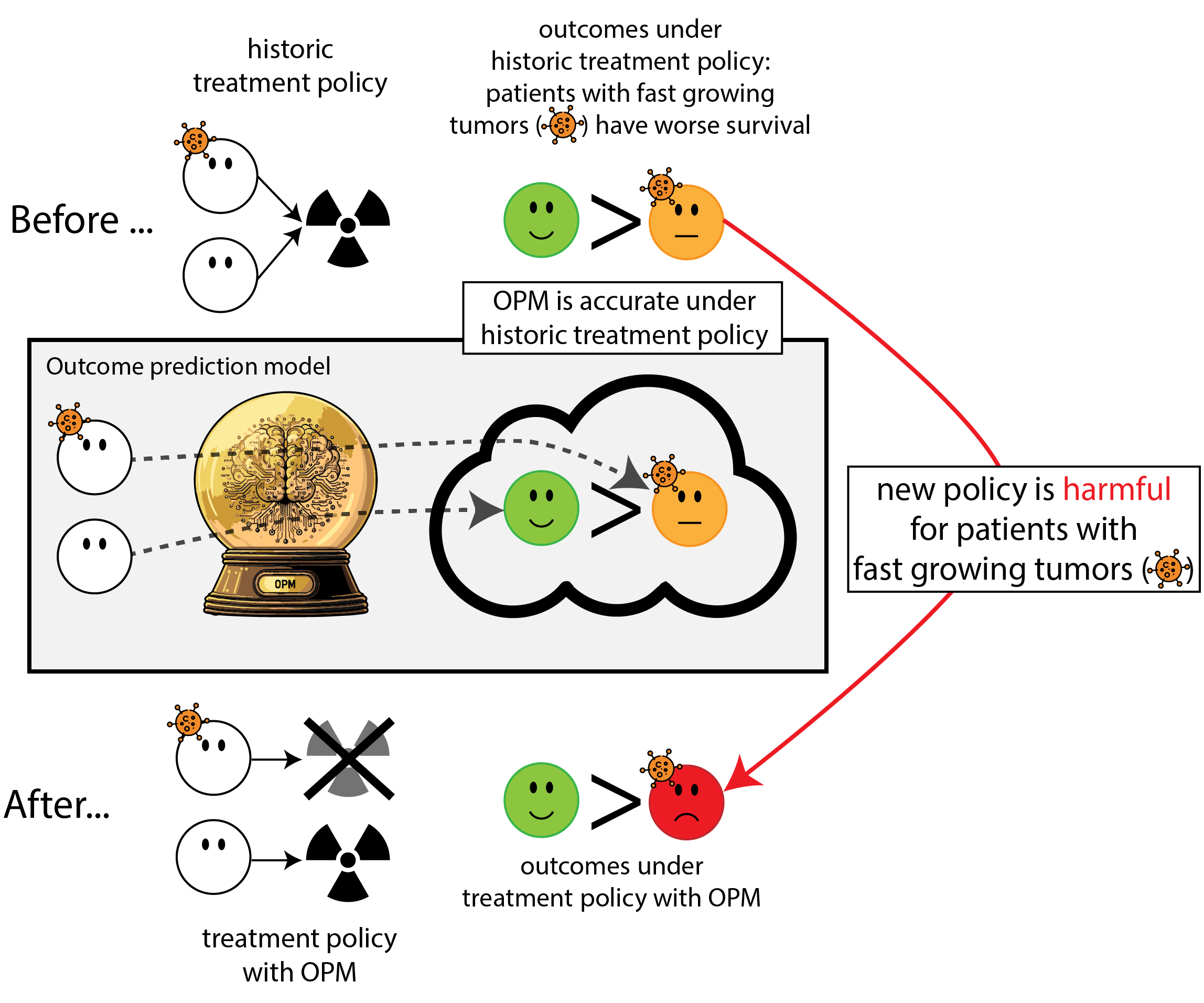

When accurate prediction models yield harmful self-fulfilling prophecies

Wouter van Amsterdam, Nan van Geloven, Jesse Krijthe, Rajesh Ranganath, Giovanni Cina; Patterns, 2025.

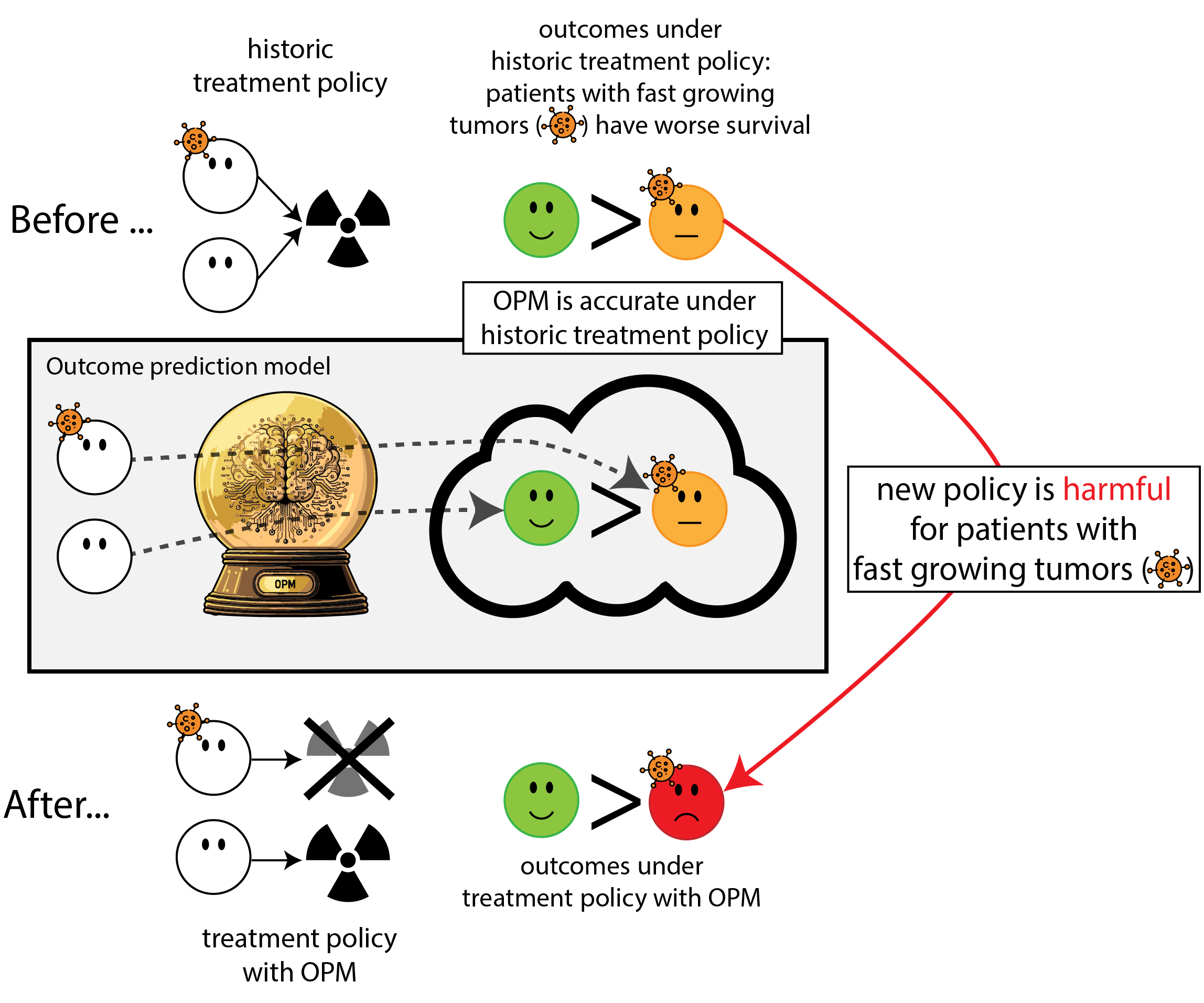

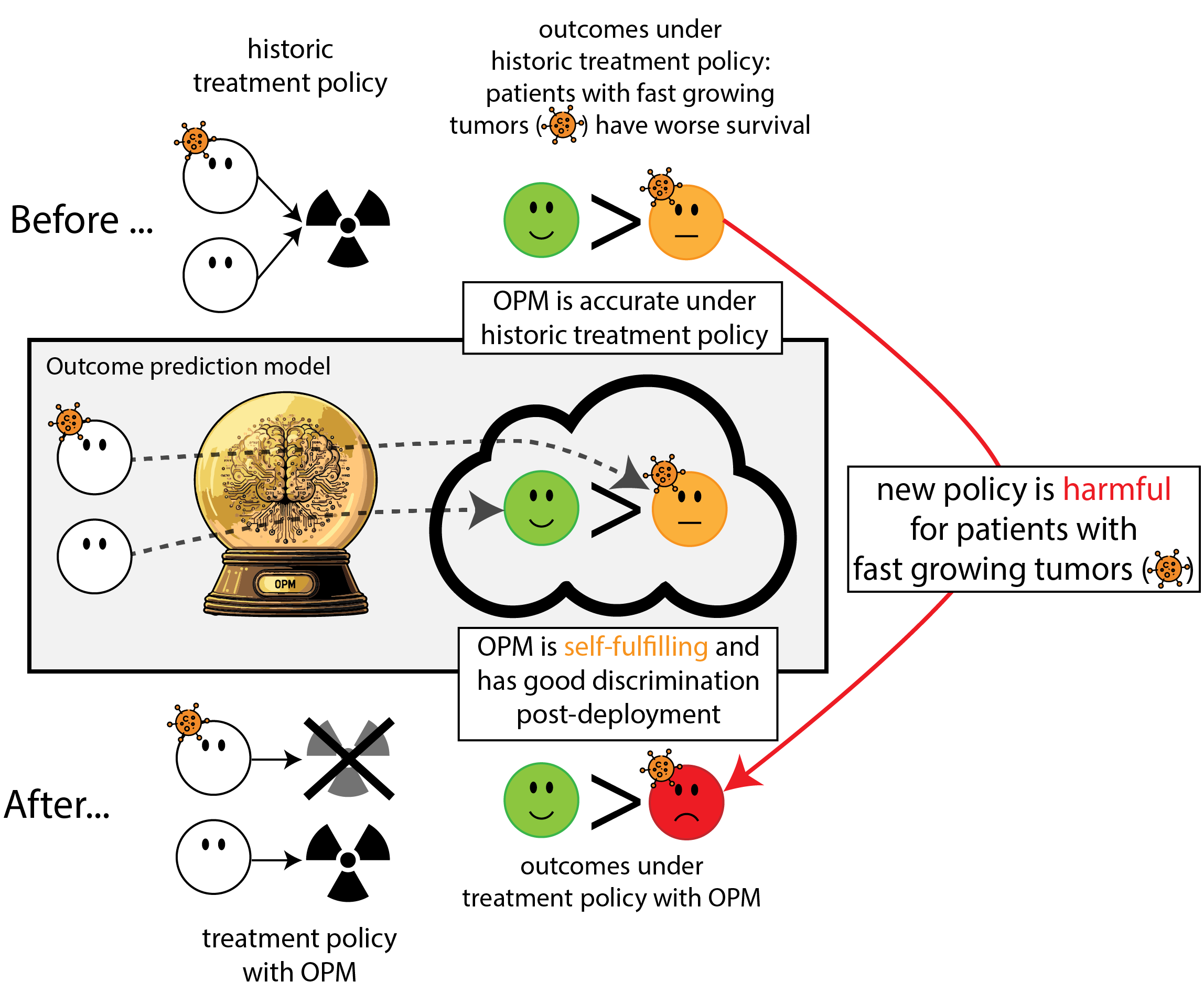

What happened here?

- had a ‘good’ model, got a bad policy

Regulation to the rescue: we need to monitor (AI) models

Let’s monitor the model performance over time

What happened in monitoring?

- the model re-inforced its own predictions (self-fulfilling prophecy)

- took a measure of predictive performance (AUC)

- mistook it for a measure of (good) impact

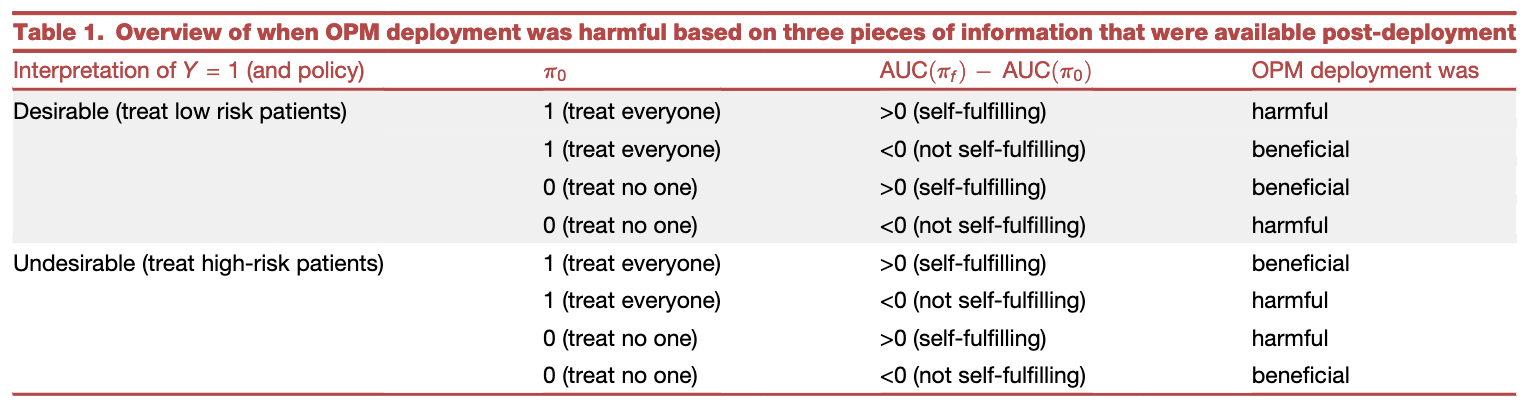

Our paper

We formalized the simplest general case

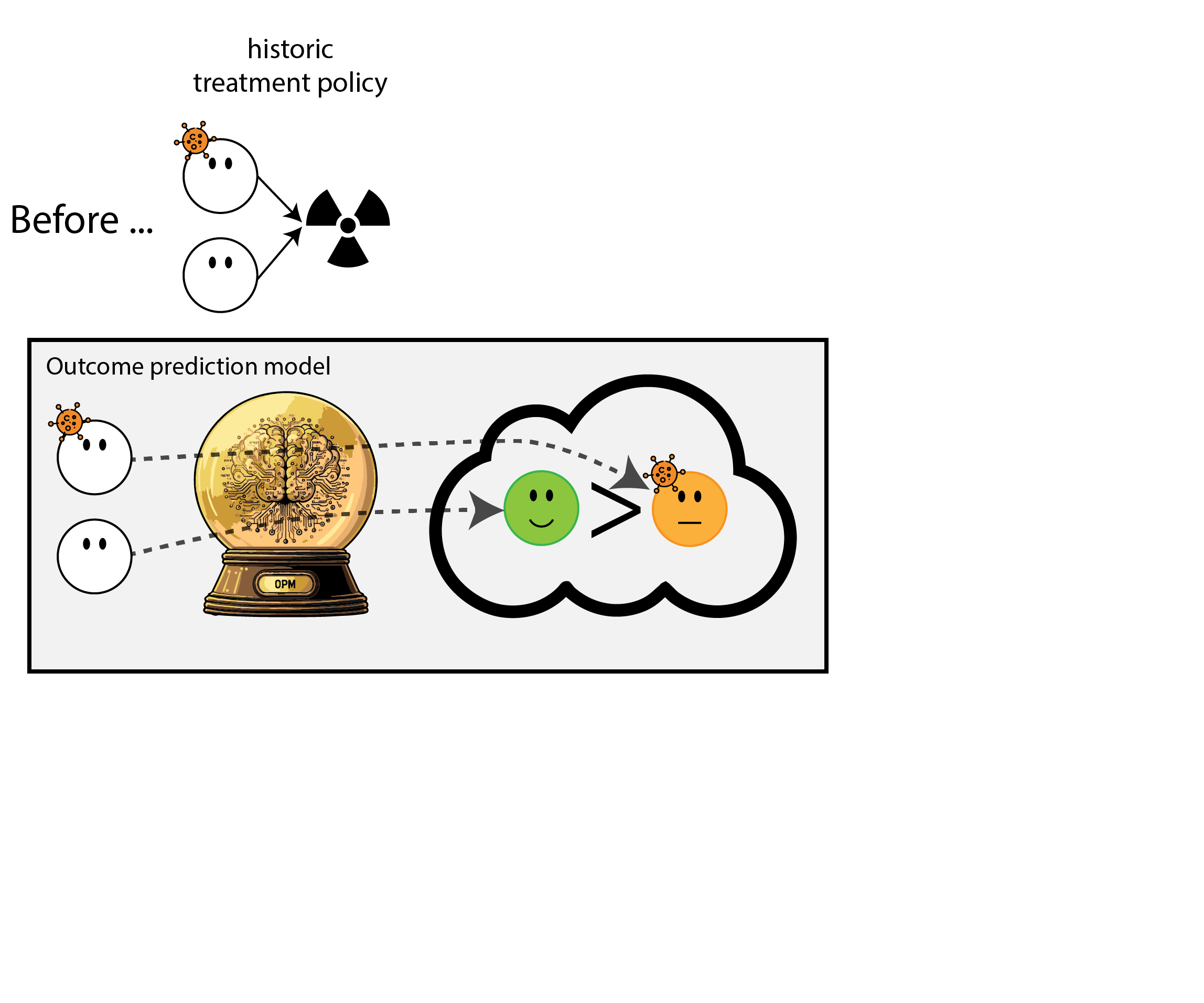

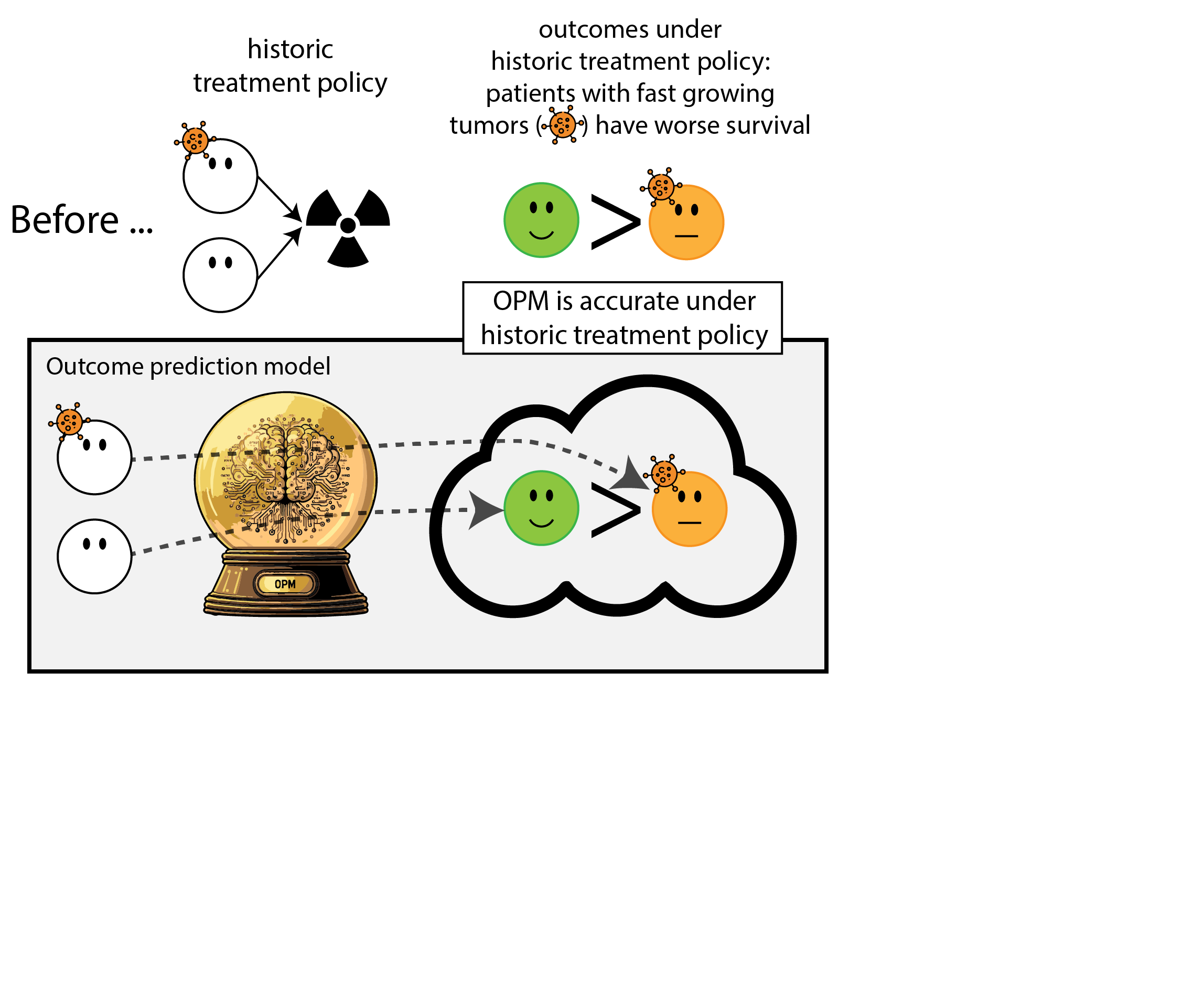

- before: everyone treated (or untreated)

- new binary feature \(X\)

- outcome prediction model: \(\mu(x) = P(Y=1|X=x)\)

- new policy based on OPM: treat when \(\mu(x) > \lambda\) (assume non-constant policy)

Define:

- harmful: new policy leads to worse outcomes (for \(X=x\))

- self-fulfilling: after deployment, re-evaluating the model yields better AUC

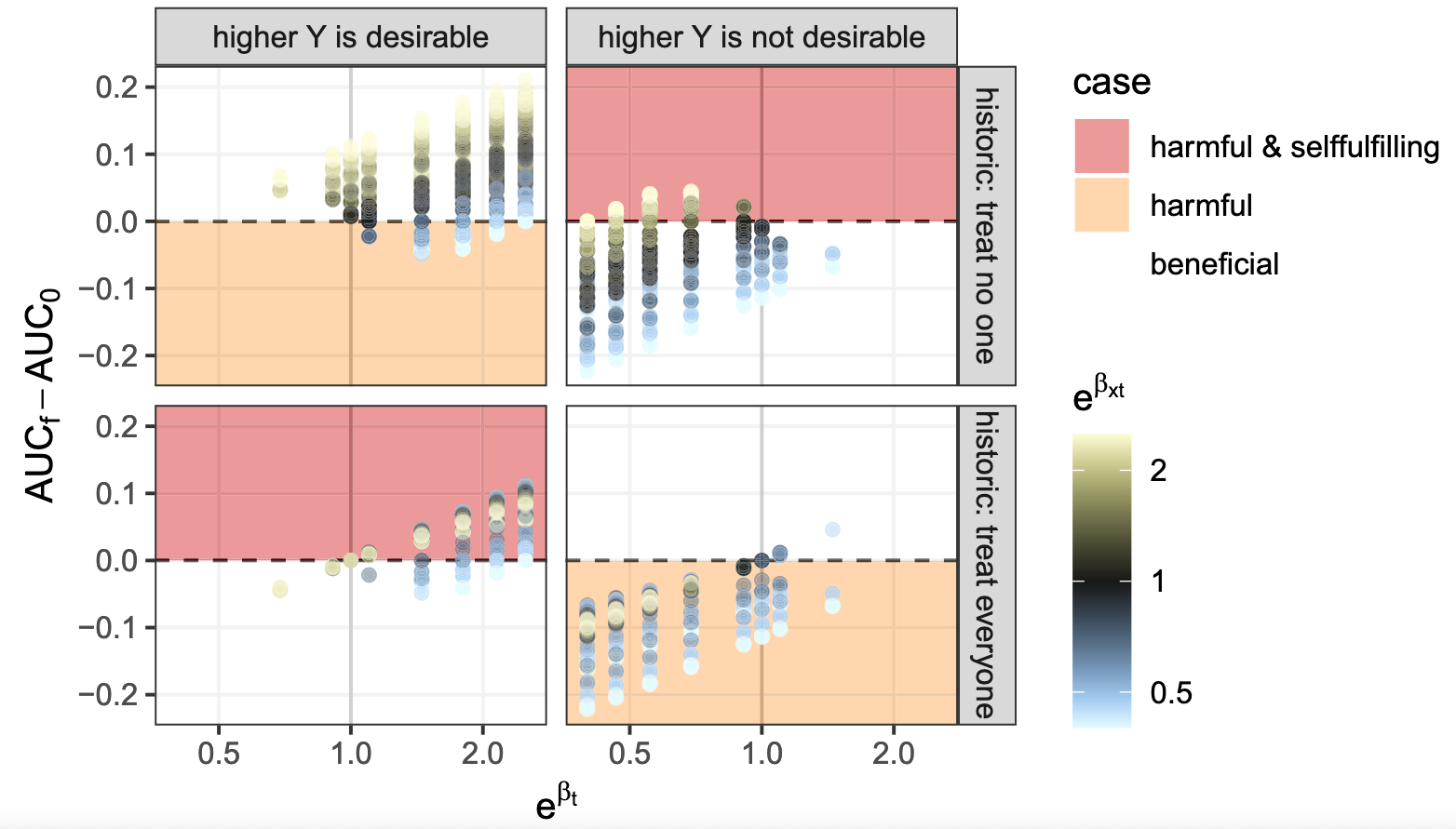

When can harmful self-fulfilling prophecies occur?

- for a grid of values of:

- baseline outcome rates

- treatment effect for \(X=0\)

- treatment effect for \(X=1\) (treatment interaction)

- prevalence of \(X\)

- historic policy and interpretation of \(Y\)

- calculate:

- expected values of outcomes (harmful?)

- pre- and post-deployment AUC (self-fulfilling?)

- question: Can harmful self-fulfilling prophecies occur in realistic scenarios?

Harmful self-fulfilling prophecies occur in cases without extreme treatment (interaction) effects

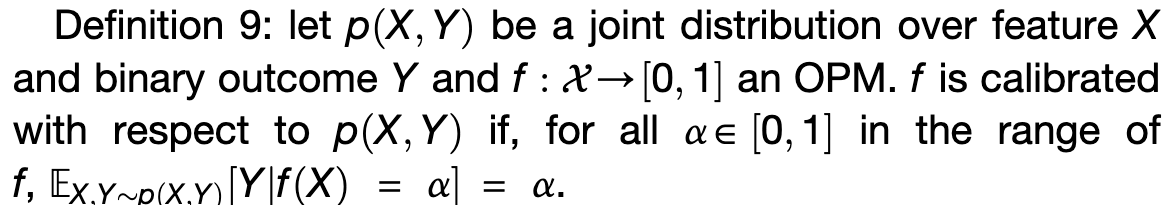

Calibration result

- ergo deployment of model was useless

Reception

Editorial

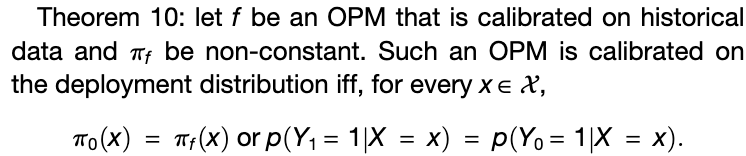

Press coverage - urgent mail

Press coverage

Press coverage

Science Media Center Roundup (7 experts)

Science Media Center Roundup (7 experts)

Withholding lifesaving treatments: When AI predicts low survival for certain patients, clinicians may deny treatment, causing worse outcomes that falsely validate the model.

Rehabilitation triage bias: AI tools predicting poor recovery after surgery can lead hospitals to allocate fewer rehab resources to those patients, directly causing the poor outcomes the model anticipated.

Post-deployment performance paradox: If real-world care improves outcomes for certain patients, models trained on historical data may appear to “fail,” encouraging withdrawal of beneficial changes and reinforcing the old, harmful patterns.

Perpetuating historical under-treatment: Models trained on biased historical data may predict poor outcomes for groups who were previously under-treated, and clinicians acting on these predictions can continue the cycle, worsening outcomes and deepening disparities.

Generalisation beyond healthcare: Predictive models used in policing can label historically over-policed demographics as “high risk,” triggering intensified surveillance that produces the very outcomes used to justify the predictions.

How about guidlines and regulation?

- reporting guidelines (e.g. TRIPOD+AI / PROBAST+AI (Collins et al. 2024; Moons et al. 2025)) do not provide enough evidence for safe deployment (“Prognostic Models for Decision Support Need to Report Their Targeted Treatments and the Expected Changes in Treatment Decisions” 2024)

- some acceptance criteria lists (AJCC) even allow for harmful self-fulfilling prophecies (Kattan et al. 2016)

- EMA and FDA are developing monitoring guidelines, mostly emphasis on predictive performance, but good performance \(\neq\) postive impact

Was the prophet heard?

Reflection

- got good attention from both scientific community and press

- us: one (of many) warnings, not guide for best practices

- need good guidance on model development, evaluation and monitoring with a view of impact

References

Deterministic evaluation of usefulness of policy

©Wouter van Amsterdam — WvanAmsterdam — wvanamsterdam.com/talks