Question

We’re evaluating a prediction model \(f\) that takes features \(X\) to predict binary outcome \(Y\). We’d like the model to be robust, meaning that it’s predictive performance is stable in different environments. To test this, the model has been evaluated in multiple testing environments (e.g. different hospitals, populations, regions, health-care settings, etc.). In each environment, we measure predictive performance with:

- discrimination: area under the ROC curve (integration of sensitivity and specificity for varying threshold \(0 \leq \tau \leq 1\))

- calibration: alignement between predicted probabilities and observed outcome rates

A. observe stable discrimination and calibration across all environments

B. observe stable discrimination but poor calibration in some environments

Answer

We’ll answer this in three steps:

- where do differences between environments come from?

- how are discrimination and calibration calculated?

- putting 1 and 2 together, answer the question

Where do differences between environments come from?

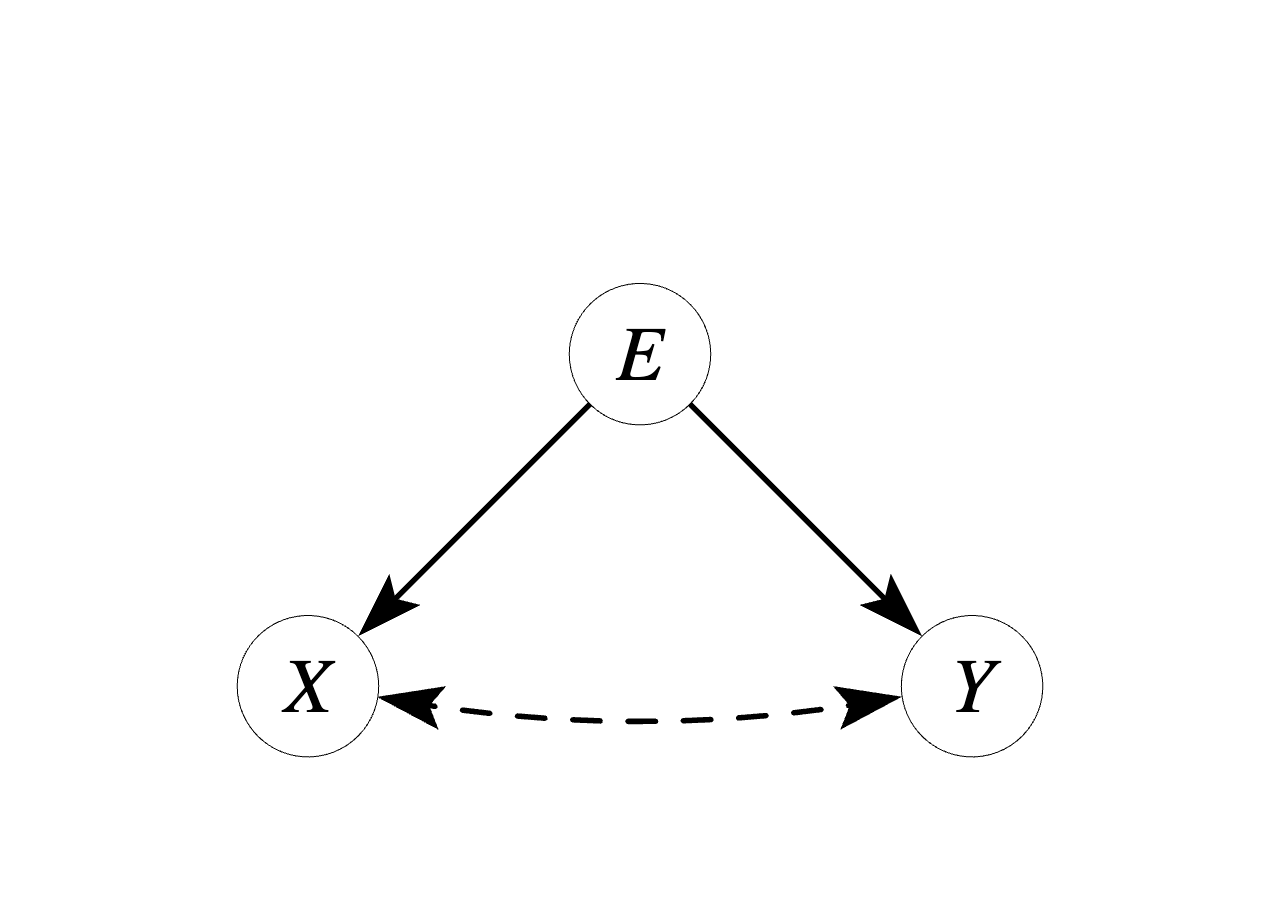

To evaluate the question we’ll first layout how exactly environments may be different. In probability statements, how the joint distribution of \(X\) and \(Y\) depends on the environment \(E\). Without making any assumptions, we can decompose the joint distriution in two ways using the chain rule (or general product rule):

\[\begin{align*} P_E(X,Y) &= P_E(Y|X)P_E(X) \\ &= P_E(X|Y)P_E(Y) \end{align*}\]

How can environments differ? Clearly, one or more of the four terms needs to depend on environment \(E\). For discrimination and or calibration to be stable, we need at least some parts of the distribution to remain the same across environments, i.e. transportable. Let’s consider the minimal differences that would lead to a change in distribution between environments. These are minimal in the sence that only one of the four terms depends on \(E\), and the others are transportable across environments. The options are:

| case | decomposition | depends on E | transportable |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | \(P(Y|X)P(X)\) | \(P(X)\) | \(P(Y|X)\) |

| 2 | \(P(Y|X)\) | \(P(X)\) | |

| 3 | \(P(X|Y)P(Y)\) | \(P(Y)\) | \(P(X|Y)\) |

| 4 | \(P(X|Y)\) | \(P(Y)\) |

How are discrimination and calibration calculated?

Discrimination measures how well a model can separate positive from neagtive cases and is typically measured with sensitivity, specificity and the AUC. Given a threshold \(0 \leq \tau \leq 1\),

- Sensitivity is the ratio of positive predictions in the positive cases: \(P(f(X) > \tau | Y=1)\)

- Specificity is the ratio of negative predictions in the negative cases: \(P(f(X) \leq \tau | Y=0)\)

The AUC is obtained by varying \(\tau\) between 0 and 1, plotting the sensitivity and specificity for every value of \(\tau\) and calculating the area under the curve.

Discrimination is a function of the distribution of features given the outcome. This means that when \(P(X|Y)\) is the same across environments, so is the model’s AUC (i.e. in case 3)

Calibration measures how well predicted probabilities align with even rates. A model \(f\) is perfectly calibrated if for all values \(0 \leq \alpha \leq 1\) that \(f\) obtains, we have that:

\[ E_{X,Y \sim P(X,Y)}[Y|f(X)=\alpha]=\alpha. \]

Calibration is a function of the distribution of the outcome given the features. This means that when \(P(Y|X)\) is the same across environments, so is the model’s calibration (i.e. in case 1)

So discrimination is stable when \(P(X|Y)\) is transportable and calibration is stable when \(P(Y|X)\) is transportable. Are they ever both? Using Bayes’ Theorem we have that:

\[ P(Y|X) = P(X|Y) \frac{P(Y)}{P(X)} \equiv P(X|Y) = P(Y|X) \frac{P(X)}{P(Y)} \]

Clearly, if any of the right-hand sides is not transportable, then neither is the left-hand side.

Calibration and discrimination are never both stable across environments.1

Except for well-engineered counter examples.

Putting it all together

Armed with this knowledge, let’s go back to Table 1 with minimal changes in the joint distribution of \(X\) and \(Y\) across environments, and fill in what will happen with discrimination and calibration.

| case | transportable | discrimination | calibration |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | \(P(Y|X)\) | stable | |

| 2 | \(P(X)\) | ||

| 3 | \(P(X|Y)\) | stable | |

| 4 | \(P(Y)\) |

Notice a pattern? Even under minimal changes between environments, at least diescrimination or calibration will change. So what happened in setting A? Given that both calibration and discrimination are stable, we can conclude that \(P(X|Y)\) and \(P(Y|X)\) are both transportable across the tested environments. The only logical conclusion is not that the model is robust against changes in environment, but that the testing environments were meaningfully different. In contrast, in setting B we have that discrimination is stable but calibration is not. We can deduce that \(P(X|Y)\) was transportable across environments, and \(P(Y)\) was not. The observed stable discrimination of the model gives confidence that even under meaningfully different environments, the model retains discrimination.

Roundup / TLDR

Environments must differ with respect to something. If the distribution of features given outcome remains the same (\(X|Y\)), discrimination is preserved, if the distribution of outcome given features remains the same (\(Y|X\)), calibration is preserved. If both are the same, the environments were not meaningfully different to begin with.

A question that remains is how these differences in environments may come about, and what to with all this in practice. On this, I wrote a paper titled A causal viewpoint on prediction model performance under changes in case-mix: discrimination and calibration respond differently for prognosis and diagnosis predictions which you can find on ArXiv

Footnotes

Counter examples may be constructed. For example, say \(P(Y|X)\) follows a mixture of beta distributions with their modes at \(\mu_1 = 0.25\) and \(\mu_2 = 0.75\) in one environment. We’re shifting \(P(X)\) across environments, so \(P(Y|X)\) is transportable and calibration is stable. If in another environment we shift \(\mu_1\) to 0, then AUC will go up; if we shift \(\mu_2\) to 0.5 the AUC will go down. We can set \(\mu_1\) and \(\mu_2\) to carefully choose values so that the AUC remanins the same in the second environment.↩︎

Citation

@online{van_amsterdam2025,

author = {van Amsterdam, Wouter},

title = {What Is Stronger Evidence of Prediction Model Robustness?},

date = {2025-04-25},

url = {https://vanamsterdam.github.io/posts/250425-robustness/},

langid = {en}

}